The History of Bread

page 3

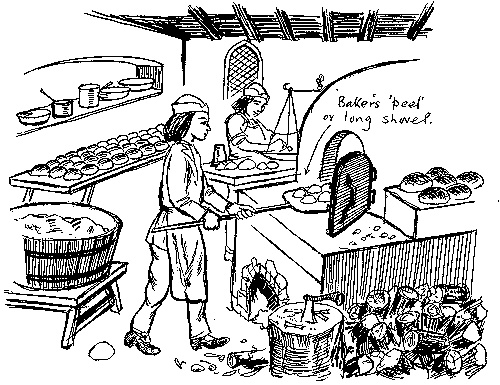

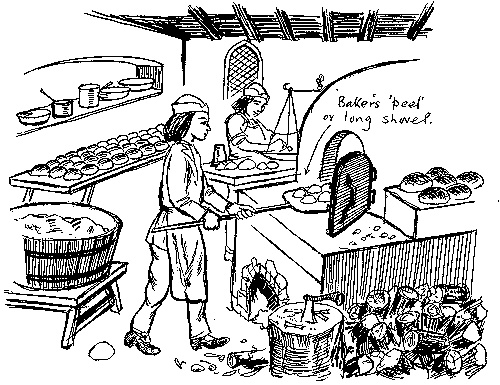

Until Modern mechanization, the tools of the baker changed but little over the centuries.

In 1310, a number of female bakers at Stratford were

arrested for sending short weight bread to London in their long

carts. As the bread was stale, however, they were let off with a

reprimand, but were forced to sell their stale ½d. Loaves at three

for 1d. In 1327 a fraud was discovered at a public bakery where the

citizens used to take their dough to have it baked. The bakers who

ran the place had secret openings made in the molding boards, and

when the people's dough was placed on the boards, one of the bakers

would secretly pinch off piece after piece from the uncooked loaves

for their own benefit.

They were exposed and caught, the men placed in the pillory with slabs of dough round their necks, while the women were sent to the Newgate prison. You can imagine that the angry populace took full advantage of the pilloried thieves, and pelted them with any foul thing that came to hand. In the time of James the First, there are records of bakers slicing their stale bread into fingers, soaking it well in water, and mixing it with the new dough. Some used tricks to deceive the Bread Examiner about weight by

inserting copper coins into light-weight bread, or by having correct

weight loaves in the shop, and keeping light-weight goods in an inner

room. But it must be said, in fairness, that the majorities of bakers

were, and always had been honest, and proud of their products.

|

An old English Bakery

An old English Bakery |

|

The invention of the steam-engine changed the industries and the

lives of the people in Britain, except, strangely enough, the milling

of flour. One miller in London who used a steam engine to drive his

machinery, found the mill destroyed by fire one day; this apparently

discouraged him from attempting to use the new steam machinery again.

Millers everywhere continued to use the ancient methods of wind and

watermills, except for a few progressive men who strove to free

themselves from the restraints of waiting on the wind and water to

drive the mill machinery. In the middle of the nineteenth century, a

Swiss engineer invented a new type of mill; abandoning the use of the

stone mill wheels, he designed rollers made of steel that operated

one above the other. It was called the reduction roller-milling

system, and these machines soon became accepted all over Europe and in Britain

|

| They were driven by steam engines, which had by now much improved, and the new method proved a great success. So popular did they become, that within about thirty years from their introduction into Britain in 1880, more than three-quarters of the windmills and watermills which had served so faithfully (if sometimes erratically) for hundreds of years, were demolished, or left to rot. Meanwhile, the development of the North American prairies, ideally suited to grow wheat, provided ample grain for the fast-growing population of Great Britain at the time of the Industrial Revolution (which in turn reduced the farm acreage here). This, together with the invention of the roller-milling system, meant that for the first time in history, whiter flour (and therefore bread) could be produced at a price that brought it within the reach of everyone – not just the rich.

As we have noted, during periods of famine or other calamities

during history, the governments of the time were quick to protect the

people's bread. For instance, in the First World War, many

regulations were passed controlling the bread trade. Experiments

began to solve problems, like keeping bread fresh for troops in the

trenches, the conservation of supplies and the stoppage of waste.

Substitutes for wheat, such as mixtures of peas, arrowroot, parsnips,

beans, lentils, maize, rice, barley and oats were used in bread

experiments.

|

|

|

|

By 1917 food-ships were being sunk by submarines to such

an extent that the nation was in dire peril of starvation. As well as

using some of the substitutes mentioned the government fixed a

maximum price for bread and issued rules for reducing waste. Bakers

were forbidden to sell bread until it was twelve hours old; no stale

bread could be exchanged; only 'regulation' flour could be used, the

millers preparing flour from such grains as the authorities provided,

and under their control. Even the shape of loaves was controlled, and

all fancy pastries were forbidden. Another order was made in 1918,

that bakers should use a proportion of up to 20 per cent of potatoes

in their bread.

In the Second World War, regulations were again imposed on the

baking industry. The 'standard' loaf was then a gray color, not very

appetizing to look at, but not at all unpleasant to eat. When you see

the beautiful loaves on sale today in all their variety of shape,

texture, and flavor, still at a comparative low price, and available

to all, think for a moment of the days, a few hundred years ago, when

it was thought that 'poor and common people should eat poor and

common bread', and only the rich should be able to enjoy the real white wheaten loaf.

|

Page 1 Page 2 Page 4

Links

Freshloaf an Old Fashioned Bakery

The Story behind a loaf of Bread

|

|

|